Introduction & Use Case:

Identifying Internet-Facing Devices Matter to Every Framework You Care About. Before we even dive into tooling, let’s anchor the importance of this work in the actual security and compliance frameworks that govern nearly every mature organization. Pretty much every major framework assumes you know which assets are exposed to the public internet — because this shapes your entire risk profile.

If you’ve spent any amount of time in Microsoft Defender, you’ve definitely seen the IsInternetFacing field in DeviceInfo and thought: “Cool… Microsoft already tells me what’s Internet-facing. Easy win!” — But is it really?? 🤔

⚡You’ll want to know for the following really good reasons…👇

🔐 NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF)

-

ID.AM-1 — Physical Devices & Systems Are Inventoried You cannot inventory devices meaningfully without knowing which ones are externally reachable.

-

ID.AM-2 — Software Platforms & Applications Are Inventoried Public exposure affects patching, configuration, and lifecycle decisions.

-

ID.RA-1 — Asset Vulnerabilities Are Identified and Documented Internet-facing assets have a dramatically higher threat frequency and must be treated differently.

-

PR.AC-3 — Remote Access Is Managed Internet-accessible services are remote access — even when not intended to be.

-

DE.CM-8 — Vulnerability Scans Are Performed External scans start with knowing what is internet-facing in the first place.

🛡️ ISO/IEC 27001:2022

-

A.5.9 — Inventory of Information and Other Associated Assets Asset inventories must distinguish externally accessible systems.

-

A.8.23 — Web Filtering / Internet Exposure Management Controls require that externally reachable systems be treated as higher-risk.

-

A.13.1.1 — Network Security Controls Segmentation, firewalls, and external exposure fall directly under this clause.

-

A.5.24 — Information Security Incident Management Planning Internet-facing devices represent higher incident probability and require forward planning.

🧰 CIS Critical Security Controls (v8)

-

CSC 1 — Inventory of Enterprise Assets External exposure is part of classification.

-

CSC 4 — Secure Configuration of Enterprise Assets Internet-facing = hardened baseline required.

-

CSC 14 — Security Awareness & Skills Training Teams must recognize risky external assets.

-

CSC 18 — Penetration Testing Internet-exposed assets are always in-scope by default for pen tests & red teams.

☁️ CIS Azure / M365 Benchmarks

-

Azure 1.1 — Ensure Public Network Access Is Disabled Unless Required Exactly the scenario we’re evaluating.

-

Azure 3.4 — Ensure VM NICs Are Not Assigned Public IPs Direct mapping to identifying internet-facing VMs.

-

M365 5.6 — Monitor External Exposure External accessibility increases alerting requirements.

🏥 HIPAA (if PHI is involved)

Even though HIPAA doesn’t explicitly say “internet-facing,” auditors consistently tie this topic to:

-

§164.308(a)(1)(ii)(A) — Risk Analysis Internet-exposed assets are higher likelihood/impact.

-

§164.312(e)(1) — Transmission Security Public endpoints require encryption and strong access control.

🏛️ CMMC / NIST 800-171

For DoD contractors or manufacturing:

-

3.1.3 — Control Remote Access

-

3.13.1 — Boundary Protection

-

3.14.1 — Scan for Vulnerabilities

Internet-facing endpoints are the first thing your CMMC assessor will ask about.

🌐 How to Actually Identify Internet-Facing Devices with KQL

(Because sometimes “IsInternetFacing = true” just lies to you 🙈)

And then—after about seven seconds of experience in the real world—you learn the truth:

- Some devices are Internet-exposed but not flagged

- Some devices were briefly exposed, but the flag didn’t update

- Some devices make outbound connections that look inbound

- Cloud networks, hybrid appliances, VPN concentrators, and IoT junk… …absolutely do not care about that boolean flag

⬆️ So today, we’re leveling up. We’re diving into a multi-signal, evidence-driven KQL detection like an attack surface samurai cutting straight to the point: “Which of my machines is exposed to the public Internet?” And we’re answering it using telemetry—not hope.

🧠 Why We Need a Better Method

IsInternetFacing relies on Defender’s internal classification. It’s great when it’s correct.

But Internet exposure isn’t a simple binary state—it’s a pattern of behavior:

- Does the device ever report a public IP?

- Does it accept inbound connections from public IPs?

- Does it listen on remote-access ports where outsiders connect?

- Does Defender think it’s internet-facing?

This blog post covers a KQL query that unifies all of these signals into one answer. Let’s break it down… 👇

🛠️ Query Breakdown

Here’s the full KQL query breakdown and comparison with comments:

❌ Using ‘IsInternetFacing == True’

DeviceInfo

| where IsInternetFacing == True

✅ Our New and Improved Query:

👉 Grab your copy HERE

// -------------------------------------------

// 1) Decide what “public” actually means (IPv4 and IPv6)

// -------------------------------------------

// Define private IP ranges for IPv4

let PrivateIPRegex = @'^(10\.|172\.(1[6-9]|2[0-9]|3[01])\.|192\.168\.|127\.|169\.254\.|224\.|240\.)';

// Define private IP ranges for IPv6

let PrivateIPv6Regex = @'^(fc00:|fd00:|fe80:|::1)';

// Lookback period

let LookbackDays = 30d;

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 2) Devices that show up with public IPs in ConnectedNetworks

// -------------------------------------------

let PublicIPDevices = DeviceNetworkInfo

| where Timestamp > ago(LookbackDays)

| where isnotempty(ConnectedNetworks)

| mv-expand ConnectedNetwork = parse_json(ConnectedNetworks)

| extend PublicIP = tostring(ConnectedNetwork.PublicIP)

| where isnotempty(PublicIP)

| extend IsIPv6 = PublicIP contains ":"

| where (IsIPv6 and not(PublicIP matches regex PrivateIPv6Regex)) or

(not(IsIPv6) and not(PublicIP matches regex PrivateIPRegex))

| summarize

PublicIPv4s = make_set_if(PublicIP, not(IsIPv6)),

PublicIPv6s = make_set_if(PublicIP, IsIPv6)

by DeviceId, DeviceName

| extend DetectionMethod = "PublicIP";

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 3) Devices whose local IP address is actually public

// -------------------------------------------

let PublicLocalIP = DeviceNetworkInfo

| where Timestamp > ago(LookbackDays)

| where isnotempty(IPAddresses)

| mv-expand IPAddress = parse_json(IPAddresses)

| extend LocalIP = tostring(IPAddress.IPAddress)

| where isnotempty(LocalIP)

| extend IsIPv6 = LocalIP contains ":"

| where (IsIPv6 and not(LocalIP matches regex PrivateIPv6Regex)) or

(not(IsIPv6) and not(LocalIP matches regex PrivateIPRegex))

| summarize

LocalIPv4s = make_set_if(LocalIP, not(IsIPv6)),

LocalIPv6s = make_set_if(LocalIP, IsIPv6)

by DeviceId, DeviceName

| extend DetectionMethod = "PublicLocalIP";

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 4) Devices that are actually taking inbound hits from the internet

// -------------------------------------------

let InboundConnections = DeviceNetworkEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(LookbackDays)

| where ActionType == "InboundConnectionAccepted"

| extend IsIPv6 = RemoteIP contains ":"

| where (IsIPv6 and not(RemoteIP matches regex PrivateIPv6Regex)) or

(not(IsIPv6) and not(RemoteIP matches regex PrivateIPRegex))

| where RemoteIP !in ("169.254.0.0/16", "224.0.0.0/4", "255.255.255.255")

| summarize

InboundCount = count(),

UniqueRemoteIPs = dcount(RemoteIP),

RemotePorts = make_set(RemotePort),

SampleRemoteIPv4s = make_set_if(RemoteIP, not(RemoteIP contains ":"), 5),

SampleRemoteIPv6s = make_set_if(RemoteIP, RemoteIP contains ":", 5)

by DeviceId, DeviceName

| where InboundCount > 5

| extend DetectionMethod = "InboundConnections";

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 5) Devices listening on classic “remote access” ports from the internet

// -------------------------------------------

let RemoteAccessServices = DeviceNetworkEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(LookbackDays)

| where LocalPort in (22, 3389, 443, 80, 21, 23, 5900, 5985, 5986)

| where ActionType == "InboundConnectionAccepted"

| extend IsIPv6 = RemoteIP contains ":"

| where (IsIPv6 and not(RemoteIP matches regex PrivateIPv6Regex)) or

(not(IsIPv6) and not(RemoteIP matches regex PrivateIPRegex))

| summarize

ServicePorts = make_set(LocalPort),

ConnectionCount = count()

by DeviceId, DeviceName

| extend DetectionMethod = "RemoteAccessPorts";

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 6) Devices Defender already thinks are internet-facing

// -------------------------------------------

let IsInternetFacingDevices = DeviceInfo

| where Timestamp > ago(LookbackDays)

| where IsInternetFacing == true

| distinct DeviceId, DeviceName

| extend DetectionMethod = "IsInternetFacing";

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 7) Merge all the signals into one “internet-exposed device” view

// -------------------------------------------

PublicIPDevices

| join kind=fullouter (PublicLocalIP) on DeviceId, DeviceName

| join kind=fullouter (InboundConnections) on DeviceId, DeviceName

| join kind=fullouter (RemoteAccessServices) on DeviceId, DeviceName

| join kind=fullouter (IsInternetFacingDevices) on DeviceId, DeviceName

// Coalesce DeviceId and DeviceName from all joins

| extend DeviceId = coalesce(DeviceId, DeviceId1, DeviceId2, DeviceId3, DeviceId4)

| extend DeviceName = coalesce(DeviceName, DeviceName1, DeviceName2, DeviceName3, DeviceName4)

// Merge IPv4 addresses from all sources

| extend AllPublicIPv4s = array_concat(

coalesce(PublicIPv4s, dynamic([])),

coalesce(LocalIPv4s, dynamic([]))

)

// Merge IPv6 addresses from all sources

| extend AllPublicIPv6s = array_concat(

coalesce(PublicIPv6s, dynamic([])),

coalesce(LocalIPv6s, dynamic([]))

)

// Clean up DetectionMethods - remove nulls and empties

| extend DetectionMethodsArray = array_concat(

pack_array(DetectionMethod),

pack_array(DetectionMethod1),

pack_array(DetectionMethod2),

pack_array(DetectionMethod3),

pack_array(DetectionMethod4)

)

| mv-expand DetectionMethodExpanded = DetectionMethodsArray

| where isnotempty(DetectionMethodExpanded)

| summarize

DetectionMethods = strcat_array(make_set(DetectionMethodExpanded), ", "),

AllPublicIPv4s = any(AllPublicIPv4s),

AllPublicIPv6s = any(AllPublicIPv6s),

InboundCount = any(InboundCount),

UniqueRemoteIPs = any(UniqueRemoteIPs),

RemotePorts = any(RemotePorts),

ServicePorts = any(ServicePorts),

SampleRemoteIPv4s = any(SampleRemoteIPv4s),

SampleRemoteIPv6s = any(SampleRemoteIPv6s)

by DeviceId, DeviceName

// Calculate Risk Score

| extend RiskScore =

case(

ServicePorts has "3389" or ServicePorts has "22", 10, // RDP/SSH = Critical

ServicePorts has "23" or ServicePorts has "21", 9, // Telnet/FTP = High

InboundCount > 100, 8, // Very high traffic

InboundCount > 50, 7, // High traffic

isnotempty(AllPublicIPv4s) or isnotempty(AllPublicIPv6s), 6, // Has public IP

DetectionMethods has "IsInternetFacing", 5, // Flagged by Defender

3 // Default

)

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 8) Assign a simple risk score and emoji risk level

// -------------------------------------------

// Add Risk Level labels with emoji indicators

| extend RiskLevel = case(

RiskScore >= 9, "🔴 Critical",

RiskScore >= 7, "🟠 High",

RiskScore >= 5, "🟡 Medium",

"🟢 Low"

)

//

// -------------------------------------------

// 9) Pretty it up for humans and sort by “what should I look at first?”

// -------------------------------------------

// Add human-readable service names

| extend ExposedServices = case(

ServicePorts has "3389", "RDP",

ServicePorts has "22", "SSH",

ServicePorts has "443", "HTTPS",

ServicePorts has "80", "HTTP",

ServicePorts has "21", "FTP",

ServicePorts has "23", "Telnet",

ServicePorts has "5900", "VNC",

ServicePorts has "5985" or ServicePorts has "5986", "WinRM",

isnotempty(ServicePorts), "Other",

""

)

// Convert arrays to strings for display

| extend IPv4List = tostring(AllPublicIPv4s)

| extend IPv6List = tostring(AllPublicIPv6s)

| extend RemotePortsStr = tostring(RemotePorts)

| extend ServicePortsStr = tostring(ServicePorts)

| extend SampleRemoteIPv4Str = tostring(SampleRemoteIPv4s)

| extend SampleRemoteIPv6Str = tostring(SampleRemoteIPv6s)

// Final output with prioritized columns

| project

RiskLevel,

RiskScore,

DeviceName,

DeviceId,

ExposedServices,

DetectionMethods,

IPv4List,

IPv6List,

InboundCount,

UniqueRemoteIPs,

ServicePortsStr,

RemotePortsStr,

SampleRemoteIPv4Str,

SampleRemoteIPv6Str

// Sort by risk, then by inbound traffic

| sort by RiskScore desc, InboundCount desc

👉 You can grab your copy HERE 👈

⚡ Below are the major components for our new and improved method—explained in normal human language, translated from “Kusto-ese.”

Think of this query as a multi-sensor perimeter alarm.

🧭 Step 1: Decide what “public” actually means (IPv4 and IPv6)

First, we teach Kusto the difference between “inside the fence” and “outside the fence” for IP addresses:

- PrivateIPRegex covers the usual IPv4 private and non-routable ranges (RFC1918 ranges like 10/8, 172.16–31, 192.168/16, loopback, link-local, and Multicast/special blocks etc.).

let PrivateIPRegex = @'^(10\.|172\.(1[6-9]|2[0-9]|3[01])\.|192\.168\.|127\.|169\.254\.|224\.|240\.)';

- PrivateIPv6Regex does the same for IPv6 (ULA ranges like fc00:, fd00:, link-local fe80:, and loopback ::1).

let PrivateIPv6Regex = @'^(fc00:|fd00:|fe80:|::1)';

- LookbackDays tells the query how far back in time to scan (30 days by default).

let LookbackDays = 30d;

💡 Anything that doesn’t match those patterns during that window gets treated as “public-ish” and therefore interesting.

🔌 Step 2: Devices that show up with public IPs in ConnectedNetworks

This is our first “hard” signal; We look at DeviceNetworkInfo and expand ConnectedNetworks, which is a JSON blob of how the device is connected. For each connection, we pull out ConnectedNetwork.PublicIP. Then We split IPs into IPv4 vs IPv6, keeping only the ones that are not in our private/non-routable lists.

We end up with:

-

PublicIPv4s= all public IPv4s observed for that device -

PublicIPv6s= all public IPv6s observed for that device

If a device shows up here, it has been seen using a public IP at the network edge (e.g., VPN, gateway, or direct exposure), and we tag it with DetectionMethod = “PublicIP”.

🛰️ Step 3: Devices whose local IP address is actually public

Next, we look for devices that are themselves wearing a public IP badge: Still in DeviceNetworkInfo, we expand IPAddresses (the local interfaces on the device). Extract each *IPAddress.IPAddress value and split into IPv4 vs IPv6 again, then filter out the private stuff using our regexes.

This way, we collect:

-

LocalIPv4s= public IPv4s bound directly to the device -

LocalIPv6s= public IPv6s bound directly to the device

If a server lands here, it means the box has a public IP assigned locally, not just hiding behind NAT. That’s a much stronger “internet-facing” signal, and we tag it as PublicLocalIP.

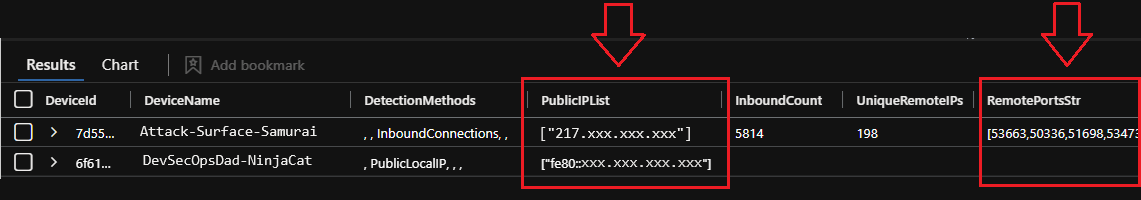

🎯 Step 4: Devices that are actually taking inbound hits from the internet

Now we move from “what IP does it have?” to “who’s knocking on the door?” We query DeviceNetworkEvents for InboundConnectionAccepted events and for each event, we look at RemoteIP:

-

If it’s IPv4, it must not match PrivateIPRegex.

-

If it’s IPv6, it must not match PrivateIPv6Regex.

Next we summarize per device:

-

InboundCount= total accepted inbound connections -

UniqueRemoteIPs= how many different sources hit us -

RemotePorts= which ports were hit -

SampleRemoteIPv4s/SampleRemoteIPv6s= a small sample of remote internet IPs observed

Then we filter to devices with more than 5 inbound connections; this is great for tackling the biggest offenders first, then you can adjust the threshold as you see fit. These are the systems that aren’t just technically reachable — they’re actually getting real inbound traffic from the internet. We tag these with InboundConnections.

If you see a device with a public LocalIP…

🔥 It is exposed

🔥 It is reachable

🔥 It is Internet-facing

😎 Pro-Tip 👉 Some devices can literally have public IPs assigned directly to a network interface, such as:

- Web servers

- Firewalls

- VPN appliances

- Load balancers

- Cloud VMs with public NICs

💡 To trap for these devices, we can look to the following detection methods and check

InboundConnections,RemoteAccessServices, andPortsetc, discussed next.

📡 Step 5: Devices listening on classic “remote access” ports from the internet

Some ports are the “VIP entrance” for attackers: RDP, SSH, HTTP(S), FTP/Telnet, VNC, WinRM, etc. We again use DeviceNetworkEvents and stick to InboundConnectionAccepted while we focus on LocalPort in:

22, 3389, 443, 80, 21, 23, 5900, 5985, 5986

We keep only events where RemoteIP is public (using the same IPv4/IPv6 logic as above).

Summarize per device:

-

ServicePorts= which of those ports are actually exposed and being used -

ConnectionCount= how often those ports are being hit

If a device shows up here, it’s not just online — it’s running interesting services that internet clients are talking to. We tag this as RemoteAccessPorts.

| Port | Use Case |

|---|---|

| 22 | SSH |

| 3389 | RDP |

| 80/443 | Web Servers |

| 21/23 | FTP / Telnet |

| 5900 | VNC |

| 5985/5986 | WinRM |

⚠️ If a public IP hits you on RDP or SSH, you’re exposed—period 👀

🌍 Step 6: Devices Defender already thinks are internet-facing

We don’t ignore Microsoft’s own smarts, we integrate it as a tertiary detection source and pull from DeviceInfo where IsInternetFacing == true to take into account in our final decision.

This gives us the built-in Defender view of internet-facing devices. Any device on that list is tagged with DetectionMethod = "IsInternetFacing" so we can see where our logic and Microsoft’s logic agree or disagree.

🗂️ Step 7: Merge all the signals into one “internet-exposed device” view

Now we glue all of this together. Full-outer-join all four detection streams plus the IsInternetFacing list so no device gets dropped just because it only appeared in one dataset. Use coalesce() to pick the real DeviceId / DeviceName when multiple join copies exist, then merge IP address arrays:

-

AllPublicIPv4s =

PublicIPv4s ∪ LocalIPv4s -

AllPublicIPv6s =

PublicIPv6s ∪ LocalIPv6s -

Build a clean

DetectionMethodslist by:-

Combining all

DetectionMethodvalues, -

Removing

empties, -

And using

make_setso each method appears only once.

-

We also carry along activity context: inbound counts, unique remote IPs, sample remote IPv4/IPv6, and the service ports we saw in use.

At this point we effectively have: “Here is every device that might be internet-exposed, plus why we think so and how it’s being reached.”

🛡️ Step 8: Assign a simple risk score and emoji risk level

With all the raw data in one place, we distill it down into something a human can triage at 8:30am with coffee. The RiskScore is a numeric score based on the following(These thresholds can be adjusted based on your specific use cases):

- 10 – If the device exposes RDP or SSH (3389 or 22). These are “break glass now” surfaces.

- 9 – If it exposes Telnet or FTP (23 or 21). Legacy and usually very bad news.

- 8 / 7 – If inbound traffic volume is very high (InboundCount > 100 or > 50).

- 6 – If the device has any public IPs at all (IPv4 or IPv6).

- 5 – If Defender itself says IsInternetFacing == true.

- 3 – Default if none of the above applied.

RiskLevel wraps that in a quick, dashboard-friendly label, illustrated below:

- 🔴 Critical – Top of the queue, you probably want to know about these first.

- 🟠 High

- 🟡 Medium

- 🟢 Low

We also derive ExposedServices so you can glance at a row and see what kind of doorway is open (RDP, SSH, HTTPS, HTTP, FTP, Telnet, VNC, WinRM, or just “Other”).

📋 Step 9: Pretty it up for humans and sort by “what should I look at first?”

Finally, we convert arrays (IP lists, ports, sample remote IPs) into strings so they display nicely in the UI, then project the most important columns up front: RiskLevel, RiskScore, DeviceName, ExposedServices, DetectionMethods, public IPs, inbound counts, remote samples, etc. Next, we sort by RiskScore (highest first), then by InboundCount. The end result is a ranked, annotated list of internet-exposed devices with:

-

What we saw (IPs, ports, traffic),

-

Why they’re on the list (detection methods),

-

How worried you should be (risk score + emoji),

-

And what kind of services are sitting on the edge.

In other words: a practical, opinionated “what’s actually exposed right now, and where should I aim my next hardening sprint?” view.

🧨 A Very Important Note: Domain Controllers Are Special (and Easily Misinterpreted)

Before you panic because your shiny new “Internet-Facing Device Detector 3000” flagged a Domain Controller with a medium or high risk score, take a breath. DCs are some of the chattiest, most-connected, and most-frequently-queried systems in any environment — so they naturally produce telemetry that looks scary if you don’t know what’s normal.

Below is your cheat sheet for separating expected DC behavior from actual exposure.

📶 Expected, Totally-Normal Domain Controller Noise

These ports and patterns are supposed to appear in your dataset. They do not indicate internet exposure.

| Port | Service | Why It Shows Up |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | HTTP | ADCS Web Enrollment, ADFS, management endpoints |

| 443 | HTTPS | LDAPS, ADFS, ADCS, and service-to-service auth |

| 88 | Kerberos | You’ll see this constantly — core authentication traffic |

| 389 / 636 | LDAP / LDAPS | Directory queries (happen millions of times a day internally) |

| 3268 / 3269 | Global Catalog | Cross-domain and forest-wide queries |

🤔 Bonus sanity check:

If you see lots of high ephemeral ports (49152–65535) in RemotePortsStr — that’s just client machines talking to the DC like normal humans. Totally benign.

🚨 When You Should Actually Worry About a DC

These are the situations where your Batman-signal should light up:

⚡ 1) The DC has entries in IPv4List or IPv6List

If a domain controller has a public IP assigned directly — you’ve found a five-alarm fire. This is a Critical Issue and likely a misconfiguration or accidental NIC binding.

⚡ 2) ServicePorts shows port 3389 (RDP) exposed to external addresses

A DC receiving internet-originated RDP hits is:

- a misconfiguration,

- a potential breach,

- or both.

⚠️ Investigate these immediately.

⚡ 3) Remote IPs from foreign countries

If your DC is being touched by IPs in countries you don’t do business with, that’s not “healthy directory traffic.” That’s “someone knocking on your root of trust.”

⚡ 4) Weird ports like 22

If a Windows DC suddenly looks like it has SSH running… Either you’ve found a penetration tester, malware, or a time traveler.

💡 Bottom Line: Interpreting DCs Without Losing Your Mind

Here’s the TL;DR your future self will thank you for:

- No public IP = Good.

- Ports 80/443 = Usually ADCS, LDAPS, ADFS — all normal.

- High inbound ephemeral ports = Normal clients doing normal client things.

- Critical risk score on a DC = Very often a false positive.

✔️ Recommendation

While you could exclude DCs from the dataset, the right move is to investigate the specific RemoteIP values to confirm whether they’re internal; if you discover NAT, CGNAT, or custom non-RFC1918 ranges, add them to your private IP regex. This ensures your report focuses on real edge exposure — not the noise generated by the busiest, most-trusted servers in your entire environment.

🛡️ Practical Security Use Cases

This query gives you a field manual of exposure scenarios on top of previously mentioned audit use cases.

📍 External Attack Surface Mapping

✔️ Immediately know which machines are reachable from the Internet.

👤 Shadow IT Discovery

✔️ Find those random Azure VMs someone spun up with public NICs and an RDP port “just for testing.”

🧱 Firewall Misconfiguration Detection

✔️ If inbound connections are hitting servers that shouldn’t be public… …fix your perimeter.

⚔️ Compromise Triaging

✔️ Inbound traffic spikes from unusual countries? You’ll see it here.

📋 Compliance Evidence (CIS, NIST, ISO)

✔️ Provides documented proof of systems exposed to the public Internet.

📡 Identify Stealth Exposures

✔️ If a device’s NIC is private, but inbound connections are still happening → NAT or unusual routing.

🗝️ Validate Zero Trust Assumptions

✔️ Trust but verify. Zero Trust cannot rely on a single boolean flag.

🤺 Why This Beats Relying on IsInternetFacing

| Metric | IsInternetFacing |

This Query |

|---|---|---|

| Uses multiple telemetry sources | ❌ | ✅ |

| Detects RDP/SSH/Web exposure | ❌ | ✅ |

| Finds NAT-exposed devices | ❌ | ✅ |

| Captures temporary / historical exposure | ❌ | ✅ |

| Sees public LocalIPs | ⚠️ Sometimes | ✅ Always |

| Evidence-driven | ❌ | ✅ |

| Ideal for compliance & audits | Meh | Excellent |

The bottom line:

IsInternetFacing is a hint.

This query is proof.

🚀 Final Thoughts

In security, reality always beats assumptions.

This multi-signal KQL approach gives you a complete, accurate assessment of Internet exposure across Defender data—no guesswork, no reliance on backend classifiers, and no blind spots created by NAT, hybrid infrastructures, or quietly misconfigured firewall rules.

Use it to:

- Hunt exposures

- Power dashboards

- Enrich attack surface reports

- Alert on real-world inbound traffic

- Catch mistakes before attackers do

And most importantly:

👉 If your device accepts inbound connections from the Internet… it’s Internet-facing—whether Defender agrees or not.

If you’ve followed the steps above, you now have a clearer view of which devices in your environment are Internet-facing — and which are silently gobbling up risk and cost. Don’t stop here. Grab your network inventory, fire up your scanner, and map every inbound point from the public Internet. Then ask yourself:

-

What unnecessary services are exposed?

-

Which endpoints haven’t been patched or reviewed in months?

-

Where can I tighten firewall rules, disable unused ports, or shift systems behind a VPN/DMZ?

Locking down these devices isn’t just about reducing noise in your logs — it’s about reclaiming control over your attack surface, cutting ingestion costs, and reducing audit risk.

So go ahead — run the scan, clean house, and harden your perimeter. If you hit surprises or want to share weird edge cases (I bet you will), ping me on LinkedIn! I sincerely hope this will help you tighten up your baseline before your next compliance push.

Stay sharp out there — and may the only open ports in your environment be the ones you absolutely need. 🔐

📚 Want to go deeper?

From logs and scripts to judgment and evidence — the DevSecOpsDad Toolbox shows how to operate Microsoft security platforms defensibly, not just effectively.

📖 Ultimate Microsoft XDR for Full Spectrum Cyber Defense

Real-world detections, Sentinel, Defender XDR, and Entra ID — end to end.

🔗 References (good to keep handy)

- 🔎Which Devices are Internet Facing?.kql

- 😼Origin of Defender NinjaCat

- 📘Ultimate Microsoft XDR for Full Spectrum Cyber Defense